I'm Sick and Tired of Sad Girl Novels

What are all these disaffected women doing to our brains?

News & Reviews Magazine

This article is part of our September edition. Read the editor’s letter to see what other fantastic writing has just been published. If you’re annoyed that it’s paywalled, then that means you wanted to read it, which means you value it. These writers get paid for what they do because their work is valuable. If you like that this type of independent media exists, please back it!

The piece you’re reading now is by Neha Kale. Neha is a widely-published writer working in many forms including criticism, journalism, essay and other nonfiction. For more than a decade, her writing on art, contemporary culture and society has appeared frequently in international and Australian publications including The Sydney Morning Herald, ArtReview, Vogue, Elephant, VICE, The Guardian, Griffith Review, Art Guide Australia, SBS, Kill Your Darlings, Gourmet Traveller, Running Dog, i-D, Wonderground, BBC and more. Neha currently writes a fortnightly column called ‘The Influence’, interviewing cultural figures about the art that has informed their lives for The Saturday Paper. She was the editor of VAULT magazine from 2015 to 2018 and is now working on her first book.

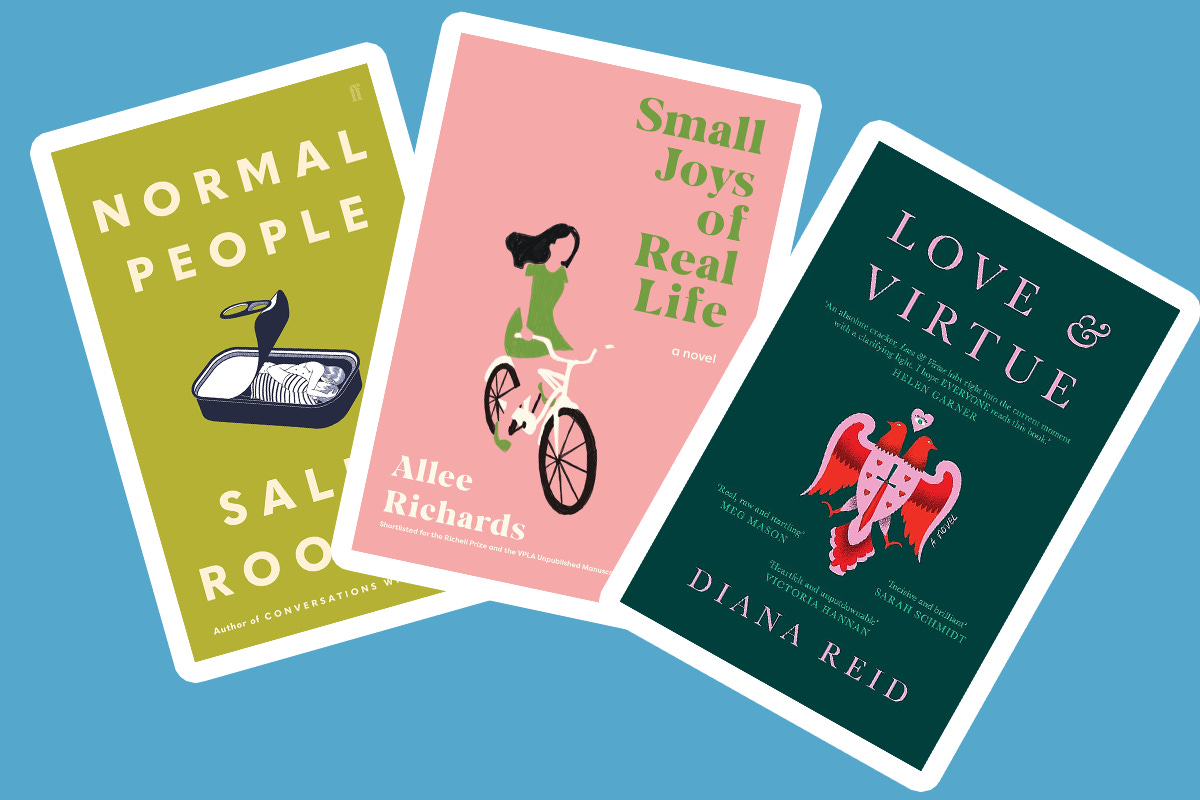

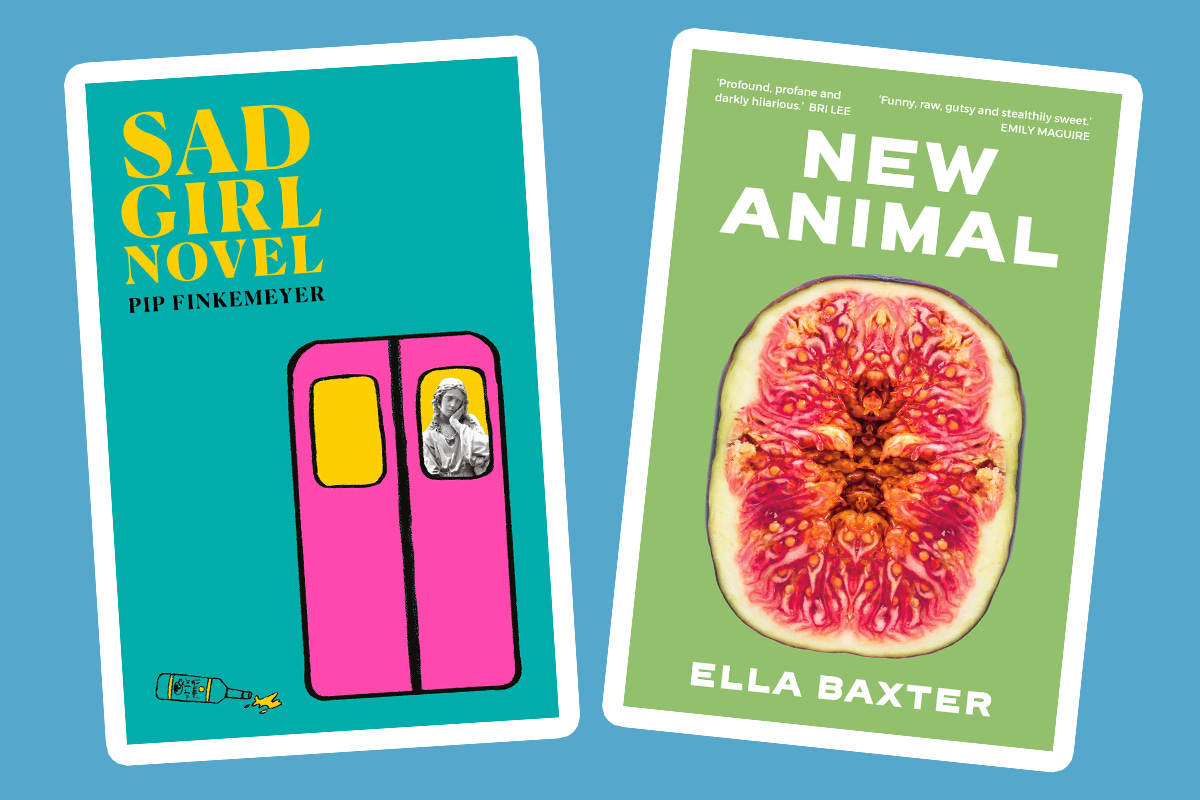

The narrator of Pip Finkemeyer’s Sad Girl Novel, Kim Mueller, is an Australian in her twenties, alone and adrift on Berlin’s Ringbahn. Kim finds the rhythm of the German railways an apt metaphor for the patterns of her life. To visit her therapist, Debbie, she makes regular dates with the city’s circular transit system and her thoughts spiral, orbiting around: Matthew, the New York literary agent she thinks she’s in love with; whether the book she’s writing is pointless; and her connection with her best friend Bel, a black-humoured historian who’s just given birth.

‘Ask Debbie about Matthew. Ask Debbie about Matthew’s invitation. Ask Debbie if your novel is stupid. Ask Debbie if your life is stupid. Ask Debbie if it’s wrong to be jealous of your best friend’s baby. Don’t ask Debbie but try to ascertain, does Debbie like you?’

In the sad girl novel, sadness is always unresolved. It’s free-floating, ambient, existential. There is so much to be sad about. There’s, of course, the problem of labour under capitalism. The problem of sex under patriarchy. The problem of love when heteronormativity feels like a dead end, when female desire so often, still, goes unexpressed and unacknowledged. I’ve read close to a dozen novels who feature narrators that feel interchangeable. They are complicated young women who want you to know that their lives are complicated. They narrate the same set of themes in a voice that’s become singular: droll, hyperconscious, winkingly self-aware, a feminist consciousness as imagined by an algorithm, digesting the terms of your life in real-time so you don’t have to.

‘Over my life, I could track the increase of my sexual enjoyment not to my partners at the time but to a skill I was honing over the years: the skill of seeing myself in the eyes of others as some sort of a fantasy,’ Kim muses.

Her tryst with Matthew, when it happens about halfway through the novel, plays out in the key of a romcom. Light streams through the window. Matthew brings her pancakes and diner coffee. They stay in bed and, in the spirit of sad girls everywhere, she calls in sick.

Kim’s interior monologue recreates the defining motif of this novel: the loop. Reading Sad Girl Novel, I started to experience my own thoughts as recursive, interpreting the obstacles Kim is facing not as problems but as conditions; truths that could be circled but never surmounted. It becomes meta. Kim spends her days reading ‘sad bitch novels’ and the novel I’m holding in my hands chronicles her attempt to write one. The sad girl writing about sad girls has turned me into a girl who is sad, just as Goya’s Saturn devoured His Son.

The sad girl novel has itself morphed into a never-ending loop of making, reading, and marketing. I’ve read so many of them. I struggle to write about them. I wonder, first, if it’s because they hit a little too close to home. Millennial women forged their adult lives in the era of can-do Girlboss entrepreneurialism. Later, the rise of #Metoo brought with it a new lexicon for old experiences. Yet June 2022 research from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency predicts that millennial women are set to earn just 70 percent of what men do by the time they turn 45. March 2022 statistics from the Harvard Business Review found that they are especially at risk of burnout and poor mental and physical health in the wake of the pandemic.

Like most women in my demographic I grew up with the belief that ambition would breed purpose, that hard work would mean rest, and that my bodily autonomy was a given. The first time I read Sally Rooney’s Normal People, I felt a jolt of recognition; the thrill of encountering literature that reflected a world in which the narratives I was sold had been leached of meaning. Lately though, I’ve been thinking more about the tropes I associate with the narrator of a sad girl novel. For example, she is alienated from work.

‘I started working at a dull company which called itself a fintech start-up but really just designed ATM screens,’ Kim observes. ‘The “fin” part was true, the “tech” and the “start-up” were just included so they could pay me less than the minimum wage in my home country.’

Eva, the pregnant narrator of Allee Richard’s The Small Joys of Real Life is an actor who can no longer stomach acting. ‘Do I get any money if I win?’, she asks her agent when she learns she’s won a Logie. ‘No just an honour,’ her agent responds. ‘Oh, well no, then. I won’t accept.’

Kim attends the Frankfurt Book Fair, wondering if she can reverse-engineer a bestseller. In the world of the sad girl novel, economic precarity has exposed the mantra ‘do what you love’ as the scam it is. For these narrators, there is no space that is free from the exchange of capital, from the fear of waking up and learning that transaction has supplanted connection.

Another trope: even friendship, the feminist promise of solace in sisterhood, is fraught. In the closing chapter of Sad Girl Novel, Kim learns that she has been deceived by Bel, who claims she told lies for her friend’s own good, to spark her writerly motivation. ‘Her face signified to me all that was good, but I let myself reconsider for a moment: what if she was bad?’ she asks.

Eve, the charismatic antagonist of Diana Reid’s Love and Virtue, which charts misogyny at an elite Sydney university, mines the narrator Michaela’s sexual assault to fuel her future celebrity. Michaela is humiliated when she discovers it. ‘The version of myself I had always tried to be around her—self-assured, opinionated—mocked me.

Can we be loyal (to our friends) if we are performing intimacy (to our lovers) all the time? What does it mean to know someone else when you are detached from yourself? Why are there so many sad girls and why do they speak in the same voice? Disaffected. Distanced. Disassociated. Especially when it comes to sex, which is almost always terrible.

In Normal People, of course, we’re supposed to read Marianne’s sadomasochistic relationship with Lukas, a Danish artist, as a foil to the safety and transcendence she experiences with her lover, Connell. But in the sad girl novel, bad sex—with a middling philosophy professor or a random man at a club or the guy who works in finance—is a readymade signifier. It is always, already a foregone conclusion: of the impossibility of female agency under patriarchy, of the way women are incentivised by the culture to submit to our own erasure. And, here, to submit to your own erasure offers a strange kind of control.

In Ella Baxter’s New Animal, a narrator called Amelia Aurelia, struggling with the death of her mother, works at a Tasmanian BDSM club, where she ties up Carl, a fifty-something man whose air she suspects is ‘managerial’. ‘This must be how method actors work; just fully inhabit the role, no questions asked,’ she deadpans. And here’s Jena, the Taiwanese-Australian narrator of Jessie Tu’s A Lonely Girl is a Dangerous Thing on how she spends her time when she isn’t playing violin:

‘I filled pages of graphic details, getting thrashed, fucked, whipped, slurped, nipped, slapped hit,’ she says. ‘I imagined my body as the most desirable thing, a machine to please men. I knew that they had more power and I saw my body as the only way to get closer to them.’

The first time I read this sentiment, I thought it was thrilling. Here was a woman of colour challenging the imperative to be palatable, to be nice—pressures that my younger self had struggled with. Here was a narrator, at least on the surface, who appears to find a sense of agency in a surrender to submissiveness.

New Animal offers sex as the antidote to grief. At the BDSM club, where the rules of consent are clearly articulated, Amelia can transcend the fact of her body. She can play out fantasies of domination and subjugation while exerting the control that’s missing from her reality. But her encounters are joyless. Instead of subversion, we get repetition, more of the same. The depressing idea central to sad girl novels is that submitting to a problem is just as valid as solving it.

The dissociative narrative mode suggests a distance and a numbing, but also an absolute knowingness. To understand the workings of gender and power is also to use it before it uses you, to withdraw emotions, to choose oblivion over transformation. To cease to care because what is caring too much if not a serious liability?

This extends to race. At a fancy waterside restaurant Mark, Jena’s lover, tells her he thinks ‘white women are too plain.’

‘I went through an African-American phase, but I’m into South-East Asian now. They have such delicate features. They are more feminine. Especially TAGs.’

‘TAGS?’, she responds.

‘Tiny Asian Girls.’

The unnamed narrator of Kavita Bedford’s Friends and Dark Shapes sits on a knoll in Sydney’s North Bondi with Katie, a friend from Punchbowl. She wryly observes how the neighbourhood’s confluence of race and class manifests a fantasy of white possession:

‘I think I feel like the biggest tourist here, growing up just forty minutes west, even with those English backpackers around, she says pointing to a group of fast burning men.’

The last time I tried to write about sad girl novels, I thought I was writing about whiteness and privilege. About narrators who can afford to be deviant and destructive and unlikeable, to reject patriarchy’s social scripts, because their bodies are already sanctioned by the culture. In this sense, Lonely Girl and Dark Shapes complicate the genre. Their female-identifying narrators, although middle class, are second generation migrants whose experiences of friendship and work and sex are freighted with the pressure to be good. The double horror of being fetishised and objectified. The burden of being ‘grateful’ for the messes they have inherited. ‘What is the point of being any kind of artist if your skin colour or gender excludes you from the choices of old white men, just because you don’t look like them and they don’t see themselves in you?’ Jena asks.

I found myself nodding. It’s an idea that I’ve thought about, written about, that I believe in wholeheartedly. But reading it, I felt trapped. Like I was stuck in a loop. As a woman of colour who shares the narrator’s class position, I resent the way the sad girl novel presumes to always know me, to bully me into understanding. Often, I am a mystery to myself but the ideal reader of a sad girl novel possesses a knowable interiority. What are these sad girls doing to me? In Sad Girl Novel, Kim chronicles her observations of race and class in the same disaffected mode.

‘Bel had taught me to refer to myself as an immigrant in Germany. It was easy to see why “expat” was problematic; white people were always called expats no matter what, and people of colour from “Western” or English-speaking countries were called expats, and extremely wealthy people from anywhere in the world were called expats too, or emigres. Everyone else was called an immigrant.’

The sentiments are different, but the way they are articulated—dry, deadpan, world-weary—share the notion that to name a problem is to extricate yourself from that problem. It draws an ethical equivalence between reflecting the workings of power and addressing the workings of power. This phenomenon, right now, is everywhere in the culture. It’s an America Ferreira monologue outlining the double standards women face in the Barbie movie. It’s the stream of books and exhibitions that celebrate the lives of overlooked woman artists. It’s a shift that, ironically enough, serves capitalist instincts which repackage resistance and sell it back to us so we can avoid the difficult work of challenging structural forces.

It’s an approach that doesn’t require much beyond consensus. That yes, the world was made by and for white men and yes, women’s lives are subjected to impossible double standards and yes, our art has been devalued and overlooked. We’ve known this for centuries. Like the language of Girlboss feminism, they are insights that have been commodified so they are self-evident, shareable.

In the sad girl novel, form and content work to affect a false profundity. Every observation is being voiced for the first time. When I first started reading a stream of sad girl novels, in the middle of a pandemic-era fever dream, I recognised parts of my younger self in the narrators. I had been Jena. I had been Michaela. I had definitely been Kim. The tropes stacked up fast. The books wanted the act of reflecting my messiness to be liberating. But what if I don’t just want to be seen anymore? What if I already know what these problems are? Each book is marketed as the first, as a transgressive and sexy debut, presuming an absence of cultural memory that condescends to its ideal reader.

One final trope I can no longer un-see is how time works oddly in these novels. They conjure a perpetual present. In Sad Girl Novel, there is barely any backstory, only one fleeting reference to Kim’s mother, as if the narrator has appeared out of nowhere. Friends and Dark Shapes, whose narrator lives in a Redfern sharehouse, notes Sydney’s colonial history in passing. Small Joys marks temporality via the rituals of a group of friends in Melbourne’s inner north, sees the passage of time as a palimpsest of gentrification in which Eva is a passive observer in the flow of history. You could say that the sad girl novel recreates the anxiety of the social media age, where everything is always happening right now. Or you could also say that when the past and future feel like abstractions it’s easy to do nothing, to surrender to inertia, to feel like moral apathy is the only logical response to our cultural moment.

I think about the proliferation of sad girls. They are stuck in a loop of bad sex and soul-crushing work and eternal alienation, endlessly critiquing the systems that trap them, promising to tell me what it means to be a woman in the world I live in but insulating me from that world instead.

Ooooft this piece is so good.

“The depressing idea central to sad girl novels is that submitting to a problem is just as valid as solving it.”

YEP! Really resonate with your last point around how these narrators seem to spring from nowhere, with little-to-no familial or other historical context beyond "it's complicated". For me, it's the complexity of intergenerational relationships explored in, for example, Jessica Au's Cold Enough for Snow (maybe a type of antidote to the sad girl novel?), that can make characters that might otherwise fall into the sad girl demographic more relatable as even being emotionally complex in the first place.

Also, I think you may even give the perpetrators of this trope too much credit in suggesting that it might link to a modern experience of anxiety or apathy. I can't help but feel when reading characters like this that it's purely a matter of whittling down the focus to a singular identity, which is ultimately flat because of it. I guess identity has been the primary preoccupation of art for the best part of a decade, but isn't it more interesting when identity is rather a prism for considering the exterior world anew? Maybe soon other readers will grow out of this phase too, and we can head somewhere in this direction.