Discover more from News & Reviews by Bri Lee

GarnerRama - Part I

The giveaway is a complete set of Garner's diaries, now in paperback, thanks to Text Publishing.

Hello and welcome to probably the single most requested theme for a special edition ever: Helen Garner.

We could do an entire year of Garner special editions but because of my trips to Antarctica and Turkey in the coming months we’re just going to start with one and pick back up in May or June. I can see this thing growing into three parts at least, like YanagiharaRama, with livestream shenanigans too. The good news for you right now is that we’re going in hot’n’spicy with a bang! focusing on her nonfiction first. Here’s what we’ve cooked up:

In my opening essay I answer a reader’s question about how The First Stone has ‘aged’, because it overlaps with some of the research I did for my Masters. Who is the Helen Garner we meet on the pages of that book? What does a close analysis tell us about Garner’s claims that the book is ‘reportage’? It’s controversial.

As you know,

live-recorded her experience of reading all of Garner’s diaries for the first time in a chat thread. (I had a ball watching this unfold.) She has now pulled her thoughts together into an essay here, ‘Shady At Best, Arrogant At Worst’ about not only those diaries, but also about the act of reading Garner in Australia, and the role Garner has come to hold in this literary scene.I don’t know if this will become a regular thing, but I had to reply to Astrid’s essay. A short riposte. (Sorry, Astrid. You can go hard serving a reply-reply in the comments if you want!)

Each month in our Nerd special edition I pen an essay replying to a reader’s question. This month there were two that overlapped and were specifically about reading and writing, which I presume the GarnerRama crowd would like, so I figured I’d take them on together. Here’s what you asked me:

How do you read so many books? Do you have a certain page target daily?

Hi Bri - my nerd question is: how do you structure your day to manage all the projects and commitments you have going at any given time? I always feel like I’m pulled in so many directions and it gets hectic so I’m always keen to know how others with heavy workloads manage their time, what their daily routines are, and any survival tips and tricks to squeeze the most out of the day. - Also thanks for your new newsletter - it’s ace! Xo

Okay, here we go! Enjoys the gifs about monkeys and stones. :)

How has The First Stone aged? Bri offers some insights.

Remember my friend Lee Tran Lam? She sent in an excellent question to the AMA portal about The First Stone which (with her permission) I’ve just laid out in full here:

Hi Bri,

This is for your Helen Garner special. I’d love to know your thoughts on Helen Garner and how The First Stone has aged.

I read it as a uni student when it came out, and felt like I couldn’t fully trust what was written, but couldn’t work out why. The writing was so confident and ‘seductive’ in a way, it reminded me of when you talk to someone who is unbelievably bright and you feel steamrolled by their intelligence and your views seem small when you try to object to something they say.

Then I read Cassanda Pybus’ edited anthology in response to the book (which featured a powerful essay by the complainants) and also some details that completely changed how I looked at The First Stone. [I think Lee Tran is referring to bodyjamming, edited by Jenna Mead.]

One key narrative of The First Stone is Helen Garner just wants to get at ‘the truth’ and the complainants’ supporters keep obstructing her and every time she approaches them, she’s rebuffed by a different supporter. This happens five, six or seven times. So you get a picture of a cabal of women trying to prevent Helen Garner and The Truth, and if feminists really care about The Truth, they would talk to her!

But then it turned out she had taken ONE person in real life and split them into 5/6/7 characters. So that sense of wall-to-wall obstruction is just one person objecting to her. And that objection seems fair, particularly as Helen Garner wrote—at the very start—a letter of support for the man accused of the sexual harassment, so the complainants felt like they weren’t going to get an unbiased perspective from her.

She also conflates certain situations—a consensual affair with a tutor is compared to what happened to the complainants as if they’re the same thing. She asks why they don’t tap into their sexual power. But being sexually harassed by the man who can determine your bursary is very different to a consensual affair with a tutor. Also, Garner does resort to the old ‘why didn’t you kick him in the nuts?’ trope.

So I think the book was already pretty dated in the 90s/2000s (although I was in the minority—people LOVED the book and I think most people sided with Helen Garner against the women). I am surprised that its reception hasn’t changed that much, especially given #MeToo (a piece Gay Alcorn wrote a few years ago was mostly a defence of the book and questioned the women’s actions).

Anyway, I’d be curious as to what you think, particularly given your expansive and expert literary/journalistic/legal knowledge!

All the best,

Lee Tran

Thank you for this fascinating and well-articulated question, Lee Tran! It helped me frame my long essay for this special edition, and helped me choose which sections of my Masters to pull out and focus on.

The very short answer is that, yes, The First Stone has aged poorly. The slightly longer answer is that, despite it ageing poorly, it’s still a rich seam for conversation both about the subject matter and writing methods. For anyone who hasn’t read the book, here is some background about the ‘incident’ from an academic article by Jay Daniel Thompson:

Five female Ormond students filed ‘informal complaints of sexual harassment’ against Dr Alan Gregory, then the College Master. Two complainants brought their harassment allegations to the police. The allegations progressed to the Melbourne Magistrate’s Court, where Gregory was found guilty of sexually harassing one of the two complainants. This charge was later overturned in an appeal hearing at the Victorian County Court. In May 1993, Gregory officially resigned from his position at Ormond. The three other women who claimed to have been sexually harassed by Gregory, but who did not seek legal redress, are not mentioned [in The First Stone].

As Lee Tran mentions, Garner saw the matter in the paper and wrote a letter of support to Gregory. Some time later she started investigating, and the main two young women refused to take part in Garner’s project. The First Stone misrepresented some things and omitted others. It was also a soaring commercial success.

By the early nineties Garner’s hit debut novel, Monkey Grip, in 1977 had been followed by numerous other books of fiction, healthy sales, columns, and award-winning journalism in respected papers; Garner earned and enjoyed the firm status of a public intellectual. When The First Stone was released in 1995 it re-ignited the ever-burning public debate around questions of sex and power. According to Bernadette Brennan’s book, A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work, The First Stone was ‘an instant sensation,’ selling seventy-thousand copies within the first few months of publication; ‘every major newspaper in the country ran columns about it’ and ‘scores of academic articles’ were published.

In her 1995 Larry Adler Lecture, later published as ‘The Fate of The First Stone’, Garner warns that ‘nothing is more suspicious than a book which appears to have succeeded,’ a statement which reflects her distrust of books written from any purported position of certainty. Instead, she sees The First Stone as ‘a series of shifting speculations, with an open structure.’ Despite this, she insists it is still ‘reportage’.

There is a difference between the first-person narrator of a text describing themselves as a journalist, and that text being a work of journalism. (Burn!) This discrepancy seems to lie at the heart of much of the criticism of Garner’s nonfiction. In consistently reasserting her book is a work of reportage, but not adhering to reportorial convention, she leaves herself wide open for attack. Garner took some huge liberties with composite characters in an attempt to avoid defamation proceedings. People felt betrayed.

For my Masters I undertook an extremely close analysis of the terminology Garner uses when encountering the subjects in the book. The following pars are dense (sorry!) but, I believe, cumulatively damning. There is a subtle but sustained difference in the way she treats different people she encounters according to gender, and it has potentially huge results. I refer to the author as Garner and the character on the page as Helen.

Helen explicitly asks Gregory ‘for an interview’ (37) then later refers to her ‘interview transcript’ (55) for information. She cycles ‘to interview’ (73) the judge who had taken chair of the Ormond council, and Mr Andrew McA-, a member of the council’s Group of Three had written to Helen ‘offering an interview’ which she accepted and later refers to as a ‘meeting’ at which she took ‘notes’ (197-110). Helen ‘interviews’ Fergus, a tutor at Ormond and later types up her notes from their conversation (121-125), and she refers to her notebook when talking to an engineering graduate about what college party culture is like (128-129). Helen is optimistic about a ‘gap in the story’ being filled by an ‘interview’ with a man called Professor J- who had ‘strong views’ on what was happening in the college and Helen arrived at his house for their ‘appointment’ (143). She drove out to ‘put some questions’ to a Mr Douglas R- who used to be a member of the college council and reflected admiringly on how he had ‘skillfully blocked; her amateurish approach, and that it took her days to ‘think clearly about the interview’ (186-191). Similarly, one morning she attends an ‘appointment’ with Mr Donald E-, an Ormond council member, and later refers to being ‘unsettled’ after this ‘interview’ (199-202). The only women afforded this more professional language of engagement are the two complainants, whom Helen asks to interview (48) via their solicitor. She does mention being nervous and early for an appointment with the law lecturer, Dr M-, but then details how pleasantly surprised she was that their conversation was so enjoyable despite their differing opinions (147).

By contrast, she is merely on the phone to women friends (15), goes to visit a young acquaintance for a conversation (38-39), and she visits an academic, Janet F- and they ‘talked’ in her ‘quiet house’ (42-45). Helen ‘visits’ Gregory’s wife at her home for two hours, but never refers to it as an interview, mentions any notes, or passes judgment about the reliability of the woman’s opinions. Helen was ‘chatting on the phone with a magazine editor’ about bad things ‘old blokes’ have said and done (61). A young woman sympathetic to the complainants ‘spoke to’ Helen on the phone (77), and Helen relays the story of a woman married to an Ormond man about how awful they are, simply by beginning ‘I know a woman…’ (80). Another opinion about people involved in the story being ‘damaged’ is given by ‘a businesswoman friend’ of Helen’s in passing and a young woman graduate ‘told’ Helen about why the complainants may have been so upset (81). After placing a ‘flurry of phone calls’ a Women’s Officer ‘agreed to speak’ to Helen, but only briefly (87). Sonya O-, a lawyer with experience as Victoria’s Equal Opportunity Commissioner, talks to Helen for almost two pages about this area of law, but it isn’t labelled as an ‘interview’ nor are any ‘notes’ referred to. Helen phones a ‘prominent feminist writer’ to ‘ask her advice,’ but this also is simply a ‘conversation’ (196).

Whether or not a conversation is considered an ‘interview’ or simply a kind of ‘chat’ or exchange of stories, may be an indication of the perceived seriousness or value of the subject. The distinction also leads to significant ramifications within this book. A large ethical challenge Helen grapples with is whether or not she should destroy some very interesting and valuable notes she took from her interview with Professor J- after he sent her a letter requesting she do so. Helen asked a magazine editor she sometimes worked with for advice, and he said legally she was not obliged to destroy the notes, but that it was a ‘moral decision’ for her (213). This is a difficult question of ethics for any practicing journalist. Eventually Helen decides to respect his request but makes it clear he had told her compelling information that went against Gregory’s interests, and Helen refers to Professor J- as ‘the one that got away’ (214).

It is an interesting proposition to ask whether this same moral standard would be applied to anyone else in the story, be they ‘interviewee’ or simply ‘woman I met at a party’. Similarly, there is a presumption of a level of professionalism but also impartiality or distance inherently applied to interactions deemed ‘interviews’ and where ‘notes’ are taken. By contrast, hearing a woman’s story as Helen stands by her side, applying lipstick in a bathroom mirror, complicates Helen’s role as reporter.

Tl;dr—as well as the flaws in Garner’s journalistic approach of using composite characters, there are also serious idiosyncrasies in the method Helen-as-investigator uses to gather and relay information. (As you can imagine, this is one of many examples I’ve pulled from my thesis. More in Part II!)

Brennan found in the archives that ‘Ten years after publication, Garner would tell Sara Dowse that she had no regrets whatsoever about writing The First Stone, except that she had lacked the courage to keep Mead as one character.’ But there’s also this interesting nugget from her 1997 Colin Roderick Lecture, later published as ‘The Art of the Dumb Question’, when she’s reflecting on whether or not she regretted writing a letter of support to the college master:

HINDTHOUGHT #1: would I write such a letter again, today, after everything that’s happened? The frank answer would probably be NO—though in a way this is a shame: it’s sad how spontaneity gets beaten out of us by other people’s responses to it. What was dumb about that letter I wrote? Its ignorance, and its naïve spontaneity.

When I picked up the pen that day, I did not think of myself as a public figure. I just felt shocked and sorry, and dashed it off. I have realised that I can’t write letters to strangers any more, without their having a meaning—and a use—beyond what I intended—because Helen Garner is not just me any longer: there’s no longer a simple link between the words “Helen Garner” and this person that I feel myself to be. Those two words come trailing clouds of meaning from which I can’t detach myself—clouds of projections—of fantasies projected on to me, or on to my persona, by people who don’t know me.

Something else Brennan discovered in Garner’s archives is pertinent to mention here: ‘the succession of draft manuscripts demonstrates that her decision to centre the book around her intuitive responses to the core events was a very conscious and deliberate strategy.’ The manuscripts show Garner deliberately breaking up more reportorial content with notes like, ‘more me here’, ‘weave me in and out’, and with irony, ‘poor me here’, and Brennan concludes that ‘The First Stone benefits from being read as a performative text.’ Garner has herself written in Meanjin a little about this distinction—between Helen and Garner:

What is the “I” in a diary? There can be no writing without the creation of a persona. In order to write intimately—in order to write at all—one has to invent an “I.” Only a very naïve reader would suppose that the “I” in, for example, the essays and journalism collected in my book The Feel of Steel is exactly, precisely and totally identical with the Helen Garner you might see before you, in her purple stockings and sensible shoes.

You can see how I spent years in this trench. It’s fascinating.

I think what lots of people misunderstood about The First Stone is that Helen is the protagonist of the story. The point of the project is to follow her questioning mind, and in this work it succeeds. The problem with this, of course, is that there are two young women who have been deeply wronged, and it is also their story. In writing the way she did, Garner made things even worse for those women. The book that catapulted her to new heights was only possible because of their suffering.

It’s telling that Garner regrets the changes she made to splitting Mead’s character, but doesn’t regret destroying the notes of the person with damning evidence against the college master. Don’t you think it’s interesting, where she decided to draw her own ethical lines between acceptable and unacceptable journalistic methods? Here’s an interesting thought experiment: how might things have gone differently if Garner had presented Mead accurately but also run the interview with Professor J-? In other words, if she’d broken different rules?

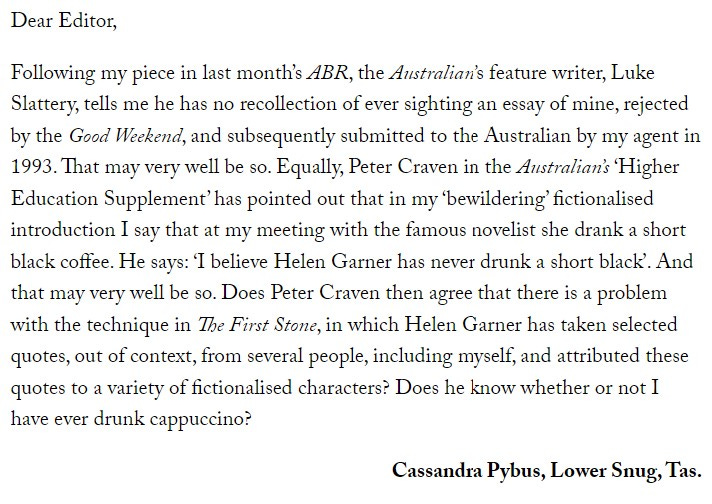

Get a load of these letters to the editor in the Australian Book Review in June 1995. Cassandra Pybus had written a critical review of The First Stone that opened with an anecdote about she and Garner having coffee together. Then other people criticised Pybus. This is Pybus’ response:

I mean, holy shit. This is some chat-throwing! This is some gun-slinging!

The reason The First Stone was such a phenomenon and controversy (things are not always both) was due to both the subject matter and the method. The subject matter was sexual harassment and assault, and a generational divide between how those things are both communicated and understood. The method was Garner’s choice to break certain rules of nonfiction. People familiar with the story claimed the liberties Garner took fundamentally misrepresented the ‘truth’ of the matters. Long story short: it was a messy story, messily told.

In Pybus’ review in ABR she writes:

‘[Garner] wants to know how she can write a book about the [Ormond College] case. I have already made a venture into the minefield of academic sexual misconduct—perhaps I can advise her? I do not think this project is a good idea. I tell her that the issue is highly charged and very complex. Ormond is not an isolated case, it is more extreme only because it has got into the criminal court. There are equally serious cases in campuses across Australia. Sexual harassment procedures are going off the rails, I say, not that the charges are trumped up, but because everyone involved is being horribly damaged. This will not be the only case to end up in court. The problem for me is the focus on the sexual nature of the offence, rather than the breach of obligations.’

Pybus says she makes many suggestions for readings and background information and critical context, but ‘the famous novelist is not really paying attention. She can see her story and I understand the pull of a compelling narrative.’

It’s harsh reading. The kind of actual shot-taking you rarely get anymore. People are wounded and wounding. The final par hits it for six:

‘There is no point in reviewing The First Stone, we are all saturated with talk about it, but I am compelled to say this: talking to your friends, listening to hearsay and reading Jung may be useful in grappling with “one of the most difficult and confounding issues of our time” [the phrase on the book’s blurb] but it is no substitute for rigorous engagement with the multifaceted context of the issue, especially when you are feeding off the devastation and distress of your fellow citizens.’

Interesting, isn’t it, that sexual harassment and assault is still ‘one of the most difficult and confounding issues of our time’. If I squint my eyes and try to see an overall shift in the culture in the almost-three-decades that have passed since the release of The First Stone, it’s that what we are now ‘confounded’ by are the actions of men, rather than some nebulous references to ‘the issue’. There is a difference. Sexual harassment was a difficult issue back then, sure, but it is now considered a difficult issue specifically because we can’t figure out how to get men to stop doing it.

As Lee Tran says, that general ‘why didn’t you just kick him in the balls?’ vibe was old then and has also not aged well. I don’t want to go down some rabbit hole of armchair psychology here but when I read in Garner’s diaries from around that time, about how she couldn’t understand why she let her then-husband treat her so badly, I felt clear reverberations to the frustrated confusion she felt towards the young women who complained of sexual harassment. The final line in The First Stone is Garner wondering why the young women were so ‘afraid of life’. It’s an odd one; they clearly weren’t. Garner created the investigating Helen so she could mine her own psyche as much as anyone else’s. Her own feminist politics on this issue were less than progressive, even by the standards of her time.

If you accept that Australian society has at least improved somewhat since the nineties, then you will look to which works helped progress us as a society, and I don’t The First Stone is one of them. It created a sort of focal point in time and spurned a huge amount of conversation, but it also gave permission for tens of thousands of people not to interrogate their outdated gender politics.

The thing I remember clearly when I was tits-deep in research was reading about how radical Garner had been: getting fired for giving kids sex ed; helping women get abortions; all kinds of cool stuff. Then the conservative types came out swinging for her, defending her in the papers because of The First Stone… she would have hated them. What did she think when the pearl-clutchers were suddenly on her side? She says she doesn’t regret things (apart from the composite character) and given her track record of being honest about her feelings, I have no reason to doubt that. All up? I remain fascinated and baffled.

Shady At Best, Arrogant At Worst: Astrid Edwards discusses Garner’s diary trilogy

I have never been drawn in by Helen Garner’s work. I didn’t enjoy Monkey Grip, I fell asleep at uni during lectures on The Children’s Bach, and I was both confused and offended by her approach in The First Stone. I left her work alone after those reading experiences, but with the republication of her early works and the release of her three diaries, I’ve been wondering if I missed something.

This piece was originally intended to explore my thoughts as I read through her diaries for the first time. Would I be enthralled by her prose? Would I appreciate her fiction in a different light? Would I finally understand what all the fuss is about? I read the diaries and you can read my live thoughts. But while reading and attempting to answer those questions, I realised I was wrestling with something bigger: I am put off by Helen Garner. Why is that?

I struggled to find the words for it until I came across this beautiful reflection on reading and not reading from Samantha Forge. Forge examines the philosophy of reading and asks what the act of choosing to read (or not read) an author means. This caused me to ask myself whether I have been ignoring Garner’s work as ‘an act of moral resistance’ against ‘the self-perpetuating machine of literary celebrity’. In other words, have I not read Garner because everyone does? The more I pondered this (an idea spurred by Yale academic Amy Hungerford) the more I realised this didn’t ring true, not least because my reading list, which I have been tracking for years, is eclectic. I read as many commercial bestsellers as I do obscure works of literary fiction.

A more likely—and apparently radical—answer is that I have not read much Garner because I simply didn’t enjoy the first three of her works I tried. Having sampled three dishes and found them not to my taste, I chose to dine elsewhere.

The related question I’ve been obsessing over is why I felt so exposed when I shared my lukewarm response to reading Garner online. And ‘exposed’ is putting it lightly—I braced for impact and assumed I would be trolled for being a ‘bad reader’, for underrating a paragon of Australian literature, for saying my quiet thoughts out loud.

I speak and write about reading all the time, and honestly, this was the first time I contemplated smudging the truth. I was tempted to pretend to enjoy Garner’s work like I felt everyone expected me to.

Imagine my surprise when I shared my thoughts and, instead of criticism, I received messages from readers and writers who have their own lukewarm takes on Garner but are not comfortable saying so in public.

There is something wrong with our literary discourse if readers and writers feel they can only ever express praise. Avoiding savaging a debut author in public is one thing. Momentum and sales and reputation matter so much at that point in a writer’s career I often choose to say nothing instead. But Garner is establishment now; in the last few years she has evolved into Australia’s literary doyenne. And critical, differing opinions matter.

I resent any widespread expectation for readers and writers to like a particular author. It negatively influences our critical culture. It stifles debate. And it makes those who have alternative opinions feel unwelcome.

Elaine Castillo, a Fillipinx American writer, unpicks the act of reading and the role of the reader in her brilliant 2022 collection How to Read Now. She articulates why conversations around who we read and how we talk about their work matter, and why we should move beyond any expectations that readers should like a certain writer.

‘… the way we read now is simply not good enough, and it is failing not only our writers—especially, but not limited to, our most marginalized writers—but failing our readers, which is to say ourselves.’ [p. 4]

Castillo interrogates everything from graphic novels to political discourse and argues that there should be space for disagreement. She critiques Joan Didion* in her essay ‘Main Character Syndrome’ and argues the mystique surrounding Didion shuts down critical debate. When everyone is carrying a tote bag with Didion’s face emblazoned on it, the problems in her work, including her questionable feminism and inherent settler colonialism, are not examined.

Garner is the closest we have to a literary icon with a cult following in Australia. Like Didion, Garner is known for writing deft prose, making it to the top of a misogynist industry, and breaking all the rules about what a woman can and cannot say. There are no tote bags yet, but there is plenty of praise.

Garner has received truckloads of criticism throughout her career. Don’t forget, in 1996 Virginia Trioli published an entire book, Generation F, that served as a rebuke to The First Stone! Garner’s diaries contain her reflections on some of that criticism. While she obviously doesn’t enjoy all of it, Garner does appreciate good criticism, as evidenced by this reflection on a less-than-positive review in the New Yorker. Garner can be interested in critiques of her work.

So, I’ll throw my hat into the ring. I found reading Garner’s diaries a duty, not a pleasure.

I adored: the references to the literary scene; Garner’s reflections on writing and finding an audience; and all the gossip about the Golden Age of publishing. Oh, for the days when writers were appropriately paid for their work!

Garner’s ruminations on creativity and intellect and are wonderful. She spends quite a bit of time reflecting on her own practice throughout, and in the second and third diaries the constant comparison between her process and that of V’s serves to draw out how structural and gendered barriers can be an added impediment.

I remain frustrated by the decision to publish the diaries without any form of editorial statement or introduction. So frustrated that I did not enjoy this reading experience. Failing to provide any context or clarification with something as intimate as diaries is the opposite of radical honesty. It smacks of hubris and is a recipe for misinterpretation. Why isn’t the reader privy to the editorial decisions guiding which entries were taken out? And to know whether included entries were edited, and if so, what ethical considerations guided that process? And to what extent entries were reordered to create a more ‘literary’ reading experience?

For example, consider the first line published in the second diary. This is a great first line. But we had a few pages of 1987 at the end of the first diary, and this great line has clearly been placed here, to open the second diary, for literary effect. I have no problem with this in and of itself—it makes for better reading. But it strongly suggests the published diaries have been carefully constructed, and there is no authorial or editorial statement indicating how this was done. I find that shady at best, downright arrogant at worst.

These are basic contextual considerations, and I can’t stop imagining some overworked and underappreciated future PhD student spending months annotating these diaries against Garner’s body of work. I am not the only one to find this difficult. Overland has done what it can and created a chronology to help readers, although that can never speak to the editorial and authorial decisions that have been made.

I fell asleep in the second diary (I have form in this regard), but like all good franchises, the third instalment is the strongest. It shares the dramatic climax and emotional denouement of Garner’s imploding marriage to V (AKA Murray Bail). The experience of this relationship breakdown is excruciating. But we shouldn’t forget that Garner is sharing intimacies of a traditional middle class cis het relationship between two people too old to be Boomers. Is what makes this relationship interesting the fact that it involves two famous literary figures?

Which brings me to the ethics of consent. V is the least sympathetic figure I have come across in my reading life in a long while, and with a few devastating relationships behind me, he serves as an avatar for all emotional bastardries. But there is no chance the real—and very much still alive—V consented to this being out in the world. Would we all be as comfortable with someone publishing this kind of intimate diary if it wasn’t a privileged older white man with the power to publish his own diaries being trashed? I doubt it.

I did perk up in some passages. I’m not going to forget the image of Garner on her knees scrubbing a toilet bowl while V drones on.

There you have it. Duty, not pleasure.

But my thoughts on Garner’s work don’t matter more than anyone else’s. Critically, my reading experience does not invalidate anyone else’s. What does matter is a dynamic reading culture, one that welcomes all reading experiences rather than going with the crowd.

* I have a cat named Joan Didion. The sad story is that I named my cat during Melbourne’s longest lockdown when I was searching for both literary and chronic illness exemplars. Joan Didion had MS and liked books and I have MS and like books… You get the picture. I was not imaginative. Castillo’s essay changed my opinion of Joan Didion the writer, and my approach to naming cats has not aged well.

Bri’s brief response to Astrid’s essay

What is so fascinating to me is that one of Garner’s earlier works, The First Stone, is one of the most divisive and controversial publications in Australia’s modern history. It catalysed countless columns and counter-columns, speeches and counter-speeches, attacks and counter-attacks. And yet here we are almost thirty years later, with a woman like Astrid feeling as though she couldn’t be open or honest about disliking the author’s work. I do believe our critical culture lacks a certain robust willingness to disagree. That’s partially why I started News & Reviews.

So! In the spirit of that willingness to disagree, I must say I was shocked that Astrid wasn’t more impressed by Garner’s ability to simply notice and reveal things. I shouldn’t really say ‘simply’, because skills of observation and documentation are those kinds of things that only feel simple when a master has them in hand. Putting aside my academic hat and my sociopolitical hat and even my author hat for a moment, when I read Garner purely as a reader, I enjoy it immensely. It is funny. The dialogue rings true. The world comes alive in small details.

I disagree a little with the assertion that not including an author’s or editor’s note about methodology is ‘the opposite of radical honesty’. I interviewed Garner for B List Bookclub last year and did a huge amount of prep listening to her previous conversations and reading the interviews she’d given about her approach. Nothing she said about her process surprised me; she clipped for length and only edited when necessary for clarity.

Many of Astrid’s frustrations about Garner’s lack of transparency mirror the criticisms people had about The First Stone not appreciating the ‘contract’ between a writer and reader if the material is nonfiction. Thinking about this distinction for my MPhil brought me to a place of irony: immense distrust in any and all nonfiction as being ‘objective’; and greater comfort both creating and consuming the form. If I’m reading a diary or memoir I know I am reading a work of a character being created. A photograph is a quick and easy analogy: what is captured may be a real record of one person’s perspective, but it involves decisions about what to chop in or out of frame, and still privileges certain views over others.

All this is to say, I read Garner’s diaries for genuine entertainment. There is enough honesty in them to strike me as being high-stakes. The Overland piece Astrid mentioned made the very insightful observation that ‘Garner’s three diaries do form a three-act staging. Helen meets V in the penultimate year of the first volume. Her contemplation of him opens the second volume, which also reveals early tensions in the relationship and marriage.’ The blue, third one is obviously the explosive end of it all. I love it! This is art! She titles the third one How To End a Story! She knows what she’s doing!

Monkey Grip was Garner taking the raw material of her diaries and, through the alchemy of work and talent, turning it into a great novel with real grit. In my opinion this trilogy is Garner taking the raw material of her diaries and, through the alchemy of work and talent, turning it into a three-act epic telling the story of how the character, Helen, moved from one stage of her life to another.

Astrid rightly asks, ‘Would we all be as comfortable with someone publishing this kind of intimate diary if it wasn’t a privileged older white man with the power to publish his own diaries being trashed?’ The answer is obviously ‘no’, we wouldn’t be comfortable. But… he is. So the result is delicious. Unethical, maybe, but my god it goes down easy if you’re simply consuming rather than critiquing.

Perhaps this makes me a hypocrite. Remember that Sad Girl Essay hole we all went down, and how the Guardian piece said ‘In any relationship, there is an expectation of privacy. There is also an expectation of respect. Violate the latter and you relinquish your right to the former.’ That is this! I didn’t appreciate it there, but here with V having actually recently published his own memoir, the playing field feels astonishingly even.

Even if there were some kind of author’s note or editor’s memo like Astrid wanted, what good would it do? Who on earth is reading a diary or a memoir looking for a factual record? We’re there for the honesty and the depth that can come when someone is completely committed to trying to communicate their individual world view. In my opinion, using this criteria, the trilogy is a monumental success.

Life, love, art, work, politics, advice, rant? Bri answers your questions!

Got a question you’d like Bri to answer? Add it to this anonymous list.

How do you read so many books? Do you have a certain page target daily?

Hi Bri - my nerd question is: how do you structure your day to manage all the projects and commitments you have going at any given time? I always feel like I’m pulled in so many directions and it gets hectic so I’m always keen to know how others with heavy workloads manage their time, what their daily routines are, and any survival tips and tricks to squeeze the most out of the day. - Also thanks for your new newsletter - it’s ace! Xo

Okay, first of all, both these questions are phrased in flattering ways, so thank you!

Realtalk: I probably don’t read as many books as you think I do. And even if I did, it is literally my job. This is what I want to say with complete commitment and clarity: if you are a writer your single most important job is to read.

I run workshops about the difference between reading ‘widely’ and reading ‘deeply’ (terms I made up, and they’re not opposites) and my own reading practices are constantly developing and growing and changing. I never have page targets, no. Some books can be raced through while others require something more like plodding. I am deeply suspicious of superfast readers. (If you’re a superfast reader, feel free to come at me in the comments and justify your position.) In general I think two things that make reading a special way of consuming art are: solitude and speed control. If I am confused or moved by something I am alone and in complete control over whether I pause to cry, throw the book across the room, or speed up to get to the twist. It’s difficult for me to imagine how someone who also has a normal job (not like me) could get through 100 books in a year and have genuinely engaged with each one. Jaclyn Crupi reads a shitton and I believe she reads well. But she’s also a bookseller so, again, reading is part of her job.

Which brings me to the second question. Essentially I think you’re asking me about productivity: How do I get so much done? But I’m also hearing something I get asked constantly, especially by early career writers: How do I manage so many different types of writing? I’ll consider these two components in turn.

A big part of my personal growth in recent years, and something that has only become clear to me through journalling, is that often my ‘best’ and ‘worst’ traits are the opposite sides of the same coin. For example, I’m proud of my impatience because it spurs me to action and I get things done, but my impatience can also make me a harsh and unpleasant human being. In the world of work projects and productivity, a big coin is boredom. I get bored very easily. If I’m not constantly moving and growing and working and changing I get frustrated and depressed. I’m so full of admiration for people who can turn up to the same job, day after day, week after week, working for someone else, so that they can make the money their family needs to live. I work much harder for myself than I ever could or would for anyone else and loathe being told what to do. I am lazy and prone to procrastination if I have to do work I don’t ‘believe in’. This is not some kind of scrappy or admirable anti-establishment thing. I’m pretty sure this is good old-fashioned immaturity. And I’m telling you this because I do not recommend trying to cultivate this approach to life. (Lol!)

What I do recommend is Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman. I listened to the audiobook of it, read by him, and found it really opened my mind about ‘getting stuff done’. It’s a trap! Life is short! When I answer more emails… more emails come! Better to ask myself: what’s the hole I’m trying to fill with all this busy-ness? If it’s artistic drive, then great. Go hard, girl! But it isn’t always. Sometimes it’s insecurity or fear or guilt. If those things are driving me, then I don’t need productivity hacks, I need to step away and ask some hard questions about the life I’m making for myself.

Some people love being able to go to work, do their work, and leave it there. I think the key to ‘productivity’ in a more meaningful sense is to figure out what your own strengths and weaknesses are and adjust your life—to whatever degree you can—to fit who you are, rather than the other way around. In my life the privilege of doing this is the trade-off for the precarity of being a freelancer. I can control my day more than a traditional employee can. What are your parameters? Where is your work rigid and where can it move for you?

The second part of your question has an answer that is simple in theory and takes a lot of work in practice: doing extremely different types of writing work forces me to more clearly articulate what each distinct approach and result needs. The voice in my legal research is different to the voice in my T Magazine column. The research for a long essay is different to the research for this newsletter. Why? How? Your question uses the phrase ‘pulled in so many directions’. I totally get this. I go through giant phases of my life feeling like this. But when I’m doing it well it doesn’t feel like being pulled in different directions, it feels like I’m Lara Croft on elastic bands, my mind and body flying through the air in whichever direction I vault.

I do not ‘structure my day’. I couldn’t even if I wanted to. Every week of my life looks different because I’m always on different types of deadlines. I’ve had to learn to let go of mental blocks about special conditions I need to create in order to work. Reading interviews with mothers helped me with this. Great writers have finished drafts perched on the edge of bathtubs while their children bathe. If they can do that, I can meet a deadline in an airport lounge.

In my mind there are three broad categories of work: events and freelancing (for money), academic and advocacy work (giving back), and the book I’m working on (my art). They interact with and benefit from each other. They each ebb and flow. I need to make enough money freelancing to be able to afford to take the immense amount of time I need to make my art. It’s a constant calibration. As I mentioned above, I get bored easily, so the constant change suits me. Some people thrive on routine. I don’t know if I would, but probably not. Not sure what’s best for you? Do yourself the respect of paying attention to yourself. Take some time and document how different work approaches make you feel.

I’ve learned about myself that my mind is sharpest in the morning, so I am careful who or what I give that time to. Through a sustained and concerted effort (and increased financial stability) I now almost always take weekends off to spend quality time with my partner and I’m sharper during the week because of it. Constant work doesn’t always mean constant productivity: most people find there are diminishing returns to hours spent at the desk in any given day or week.

In the end all the things I could say are variations on the only two tricks: knowing yourself, and having enough money to live and work according to that knowledge. I sincerely wish you all the best! I hope what you’re squeezing out of your day is juicy.

Upcoming Special Edition and Giveaways

The winner of last week’s giveaway, a copy of Lovers Dreamers Fighters by Lo Carmen, is #115 out of 135. I’ve emailed you, Rebecca Clare Page!

This week’s giveaway is a complete set of Garner’s diaries in a new paperback format, thanks to Text Publishing. Enter with your name and email address here and I’ll draw a winner at random next week.

The next edition of Style will be out Wednesday 30 November, and it’s huge. I’ve changed my three words, and I’ve bought a lot of stuff I want to tell you about.

Nerd special editions in February will be all Antarctica stuff somehow, but it’s pending Wi-Fi on the ship, which is apparently very unpredictable. I’m problem-solving! Stay tuned!

Subscribe to News & Reviews by Bri Lee

Smart takes on books, news, and culture. Straight from Bri's desk in Sydney to your inbox each Wednesday at 5pm.

Urgh Bri this is why I subscribe to News&Reviews!!! I've only read some of Garner's short stories (From "Everywhere I Look") but this was fabulous. Feminist/ethical/philosophical debate!!! Discussions and insights into Australia's literary scene from two brilliant Australian writers!!! Exploration of creative process and the boundaries of fiction/nonfiction!!! Productivity/life balance content!!! Thanks so much!

Garner has always walked the fine line between fiction and non-fiction. I don’t try and work out what what is real and what isn’t because the ‘truth’ will always be through her experiences and therefore there will always be elements of fiction.

When I read her diaries I try and put all the noise and criticism aside and just be taken along for the ride of her amazing observation. I’m surprised with how affronted I feel with Astrid’s criticism of the diaries even though I rationally see the points you are making. My initial reaction is, do we have to critique everything, can’t some things just be for pure enjoyment? But I don’t know where you would draw the line. Astrid, would it make you feel better if it wasn’t marketed as non-fiction?

The part about being scared to say you don’t like a popular author has made me realise it feels so much more personal to criticise an authors work compared to just not liking a musicians song or album. I wonder if that’s because of the effort that we know goes into writing something? I never give less than 3 stars on Goodreads (your favourite Bri) even if they are an international best seller.

I completely agree that we would all be up in arms if it wasn’t a straight white male who was portrayed in the villain but holy moly isn’t it just juicy sweet revenge for how awfully he treated her. I love the diary entry where he asks her not to write about him in her diary. ooooops!

Thanks for sparking such an interesting discussion!